I started this blog with a plan: I would write every day, and post something, no matter how good, and over time I would find my voice. But when I tried, I discovered something: I struggle to put my ideas into words, at least on paper.

In person, I can let the cadence of the conversation guide me to topics. ("so why not start a podcast?" Quiet, you.) The same phenomenon happens on X: everyone is engaged in a discourse, and I find that I can write quite fruitfully on the Topic of the Day, partially because I have managed to grow a modest audience that can be counted on to engage on some level with what I put out there. The same isn't true of blogging, but that's only part of the problem.

After months of repeatedly throwing myself at the wall, I've identified two major causes for this: The Three Stooges Effect, and Silent Voices.

The Three Stooges Effect

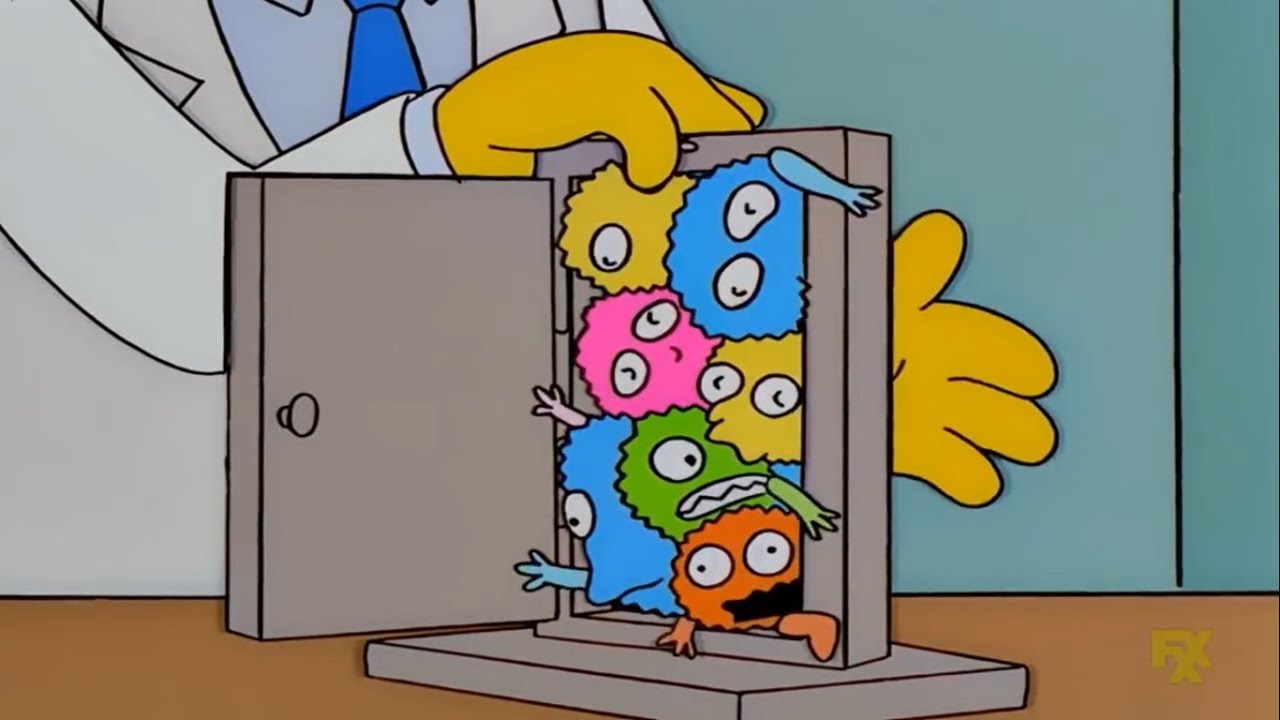

The Three Stooges Effect is simple enough to explain. In season 12, episode 11 of The Simpsons[1], Mr. Burns is informed that he has so many diseases they all cancel each other out, like a bunch of knuckleheads all trying to go through a door at the same time.

If you can write anything at all, this kind of mental constipation can be resolved by writing, and writing, and writing anything at all; eventually the sheer volume of writing will ensure that you've at least laid the groundwork for every major topic you want to cover. At this point, you can go back and weave threads between ideas, or edit content to say what you really meant more clearly, or write about new thoughts or elaborations on existing thoughts that the process of writing exposed within you.

I thought that I could push through this barrier through sheer force of will, but instead bounced off it repeatedly[2].

Clearly, there was (or were) some other problem to overcome.

Hunger, jigsaw puzzles, and art

There are three stories that spring to mind when I think of how to describe Silent Voices. In a fitting twist, these are both explanations of what a Silent Voice is, and only explainable because I have learned to listen to Silent Voices.

I don't believe I can do these voices justice by simply providing a clinical description of them; that would strip them of their import. But, through illustration, maybe you can begin to see the moon instead of the finger pointing at the moon.

Learning to hear my hunger

When I was in High School, I ran out of math and science classes to take. So, I speedran my remaining credit hours, and went on foreign exchange for a year.

Further, my already uneasy relationship with food prior to then was made worse by the stress of cramming two years of college prep into nine months, working multiple part-time jobs, and having a rudderless summer after Junior Year. My weight ballooned.

In practically every country outside the U.S.[3] people have a better relationship with food than we do, and from the moment I stepped off the plane, my weight plummeted. From a high of 242 pounds, I shed roughly two pounds per week for the next 30-some weeks, coming to rest at a svelte 175 pounds.

Along the way, I discovered a lot of truths about my body that I had been silencing with food. Being lighter made me more agile; more aware of my body's position in space. I snacked not because I was hungry, but because I was displacing feelings of my identify being unmoored—from uncertainty about classes, or what I was reading, or what my goals were. I didn't snack when snacks weren't present; not having food readily available put me in the position of having to face my feelings head-on instead of displacing. And so on.

More pertinent, though, was that over time I came to recognize the feeling of satiation: "this is the amount of food I need to eat to be full enough to get me to the next meal." Satiation is a strange feeling to discover when all your life you have eaten until some other signal was met: your plate is empty, or your curiosity is satisfied (an experience that happens most commonly at buffets and potlucks), or you feel gorged. Satiety is a slow burn: your lack of hunger increases, and is replaced by a rising awareness that you can feel food present in your stomach, and if you slow down and digest a bit, will reach a point where you can be comfortable not eating in the near future.

"Fullness," by contrast, is best experienced during feast seasons: Christmas, Thanksgiving, occasional parties. When the drinks flow freely and you know there will be no demands on your attention for the next two or four or thirty hours, and you can keep the conversation going or curl up on the couch and digest your bolus, like a snake passing a rat under a heat lamp. Many Americans have unconsciously trained themselves to listen for the klaxon siren of "fullness" as the signal to stop eating, and over time distend their stomachs and their appetites such that more and more food is needed to set off the alarm.

By learning to "hear" the quiet voice of satiety, I became not only more in touch with my body, but also with the concept of non-verbal signals inside the body, writ large.

Jigsaw puzzles and the bicameral mind

I have a particular set of skills which make me a nightmare for jigsaw puzzles: visual acuity, color accuracy, patience, and mild perfectionism. On a recent shopping trip, my wife and I picked up a pair of puzzles that turned out to be unexpectedly difficult: one, comprising large expanses of flat colors, and the second, a version of Van Gogh's Starry Night overlaid with gold highlights.

While working on the puzzle, I had time to mentally step back and observe what I was actually doing. On the one hand, there was the obvious sorting and arranging: this piece has the dark greens and browns of the bush on the left; that piece is part of the town. Further, there were processes of orienting via other, verbalized (or verbalizable) features: the brush strokes are rising to the left, this is this blue, not that blue, and so forth.[4]

But as my wife and I completed the puzzle's easier portions and got to the sea of blues and yellows making up the top 70% of the painting, something curious happened. While her method of fitting pieces involved finding an easy sub-problem and then attacking it combinatorially, testing each piece's contours against every other piece's, I did something quite different.

I would look at a likely portion of the puzzle, scan over the collection of available pieces, reason about which pieces could possibly fit (this one has the same dark blue; that bit of gold lines up with this bit of gold), and then, without conscious effort, grab a piece seemingly at random and

drop

it

right

in

place.

Does the artist make art consciously?

One final story before I get to the point of this essay.

Recently, I was talking to Kendric Tonn on X. Kendric is a classically-trained fine artist (he paints for a living!) and is reliably engaging and insightful on the topic of fine art.

In this case, Kendric was replying to this post, which states:

I'm [not gonna lie,] one of my biggest peeves is when people say "the author doesn't understand their own character"

Like they're the author, the character is ultimately their vision

You can 100% disagree with that vision, but if there's one person who understands them, it's them

Kendric responded:

This seems wrong to me; I could wave towards examples, but perhaps it's easiest to say that sometimes I look at my own paintings, when I've gotten a little distant from them, and seen things that appear to be good decisions, but not ones I ever consciously thought about

My "yes, and" response to Kendric (expanded for this format) was basically "don't sell yourself short": the part of you that puts things into words should not be confused with "you." That is, you as writer, writing into a character a personality trait that you didn't notice verbally, or you as a painter, choosing colors or applying paint just so in a way that you would struggle to vocalize, is still you. "You" are not your voice; you are a collection of gestalt understandings of the world around you, and the ways you process those understanding and manifest yourself into the world are not limited to what you can speak.

Learning to heed silent voices

What does this have to do with blogging, then? Well, if I've failed to show you the answer so far, let me try to make it explicit.

If you engage only the part of you that creates a "mental voice" when writing, what you will produce will probably be no better than a technical manual: dry and formulaic. There is a time and a place for that, but if your goal is expression, especially of those things that are intuitive or ineffable or very difficult to eff, then I tell you: most people are not configured to be able to do so by mere words.

When you lift weights for the first time, you have to engage muscles you barely knew existed until then. The day after doing a new exercise is often revelatory: parts of your body that had never made themselves known suddenly begin screaming.

Similarly, when writing for the first time, you have to "build muscles;" you have to figure out forms and mental pathways and how to listen to your motivation and your silent voices in ways that may be foreign, especially if you've never done so.

"Why does my brain hurt?" asks Neo.

"Because you've never used it," replies Morpheus.

Coming off several years working at a job where most of my writing was formulaic (technical writing, business emails; generally, stepping down the high voltages of hard-won objective knowledge to the low voltages that could be understood by unfamiliar users), my brain had become flabby and weak. Or, at least, weak compared to my aspirations.

I would like to write quickly, and talk about things that I don't know the full answer to, in ways that are more akin to painting a picture or doing an interpretive dance than writing a manual.

In order to do so, I need to find and train those mental muscles that I've neglected,

and put their silent voices in touch with the part of me that generates words,

and be open to tapping into those voices via side-channels (by making drawings or writing code or moving through space)

and then, only when those silent voices are screaming at me what they see and what they know,

will I be ready to write.

It turns out that I have never actually seen this episode. Repeated exposures to this scene have ingrained it in my memory, to the point that I incorporated it into my memory. ↩︎

It turns out there's another mental barrier also in this vein: the desire for pertinence; wanting every single essay to be an absolute banger that strikes at the heart of the topic. Some authors manage to present a small, tight collection of essays that accomplish this goal. What they don't generally show you is all the other writing that got them to the point where they could write small, tight essays. I may say more on this topic in a future post. ↩︎

At the time. U.S. and global eating habits have in many cases converged uncomfortably. ↩︎

Building jigsaw puzzles is a fantastic way to learn to appreciate art. There is nothing quite like taking in a piece of fine art via staring closely at all of its individual components for ten or more hours. ↩︎